Radio Edit:

We made it! This is the last track in Vol. 01: The Case for Alter Egos. It’s been such a whirlwind month kicking this project off, and I’m so excited to connect with you all. Last week, we dug deep into drag and explored the alter ego through gender. (You can read it here if you missed it!) For this track, let's consider experiencing different parts of the self through culture. We’re only focusing on one artist this week, Chicago’s very own, barrier breaking Theaster Gates.

Track 04 is about representation. If you can’t find yourself in the past, become the bridge itself. Blow up the canon while you’re at it.

Extended Play: Theaster Gates

Theaster Gates contains multitudes. As an urban planner, he revitalizes buildings, city blocks, and neighborhoods into arts incubators, studios, and maker spaces. As a sculptor, he makes art objects that highlight the traumas and triumphs in Black history. As a performance artist, he collaborates with fellow musicians and gospel singers to form the The Black Monks, infusing storytelling and spirituality into his sound. As an educator, he promotes social engagement. His website bio puts it best: “Gates smartly upturns art values, land values, and human values.” His work transcends the physical form, as his main creation is opportunity. Based in his hometown of Chicago, his impact is global but his mission is local—to provide opportunities for creators of color and make the art world more inclusive.

Shoji Yamaguchi

Theaster Gates' first exhibition, Plate Convergence, took place in 2007 at the Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago. The show displayed 50 plank-shaped clay plates that were also featured in video projections of a recorded dinner party. During the opening night, Gates presented the ceramics as the work of his mentor, Shoji Yamaguchi, a master potter from Japan who moved to Mississippi after WWII’s nuclear bombing of Hiroshima. As Gates told the story, Yamaguchi married a Black civil-rights activist and settled down to have a family. Together, they created a flourishing arts commune, where they shared their knowledge and hosted dinner salons, creating community around political discussion and cultural exchange. Tragically, they both died in a car accident, and their son founded the Yamaguchi Institute to continue the legacy of his parents’ work. Shoji Yamaguchi’s son attended the opening, bridging his family history to the present exhibition.

It was an extremely compelling story, and one that everyone believed. Except it was totally false. Shoji Yamaguchi was the Japanese alias of Theaster Gates.

As part of the evening’s festivities, Gates hosted a fusion dinner of “Japanese soul food”—with dishes like black-eyed pea sushi, served on the ceramics his mentor made. Patrons and collectors ate it all up—they were enamored by the work and the story Gates so charismatically told. In a 2014 article in The New Yorker, Gates described the reaction: “People would be so reverent, ‘Oh my God, these pots are so great!” At the end of the night, Gates revealed that the story was a fabrication, the son was a paid actor, and he himself created the pottery.

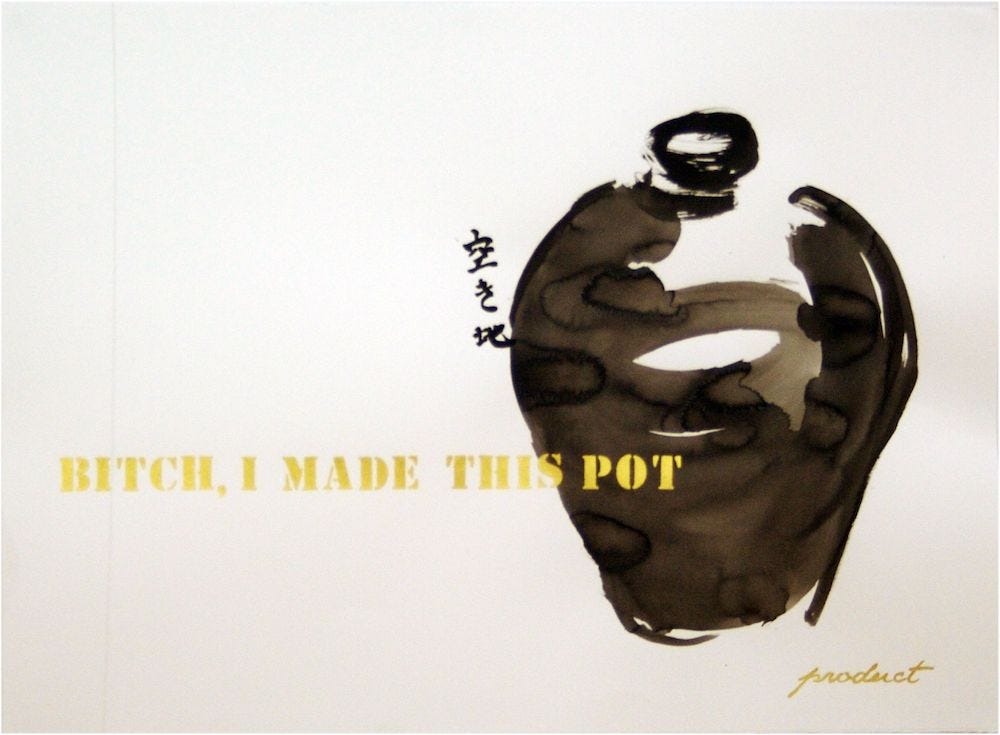

Apparently, no one felt salty at being duped. Instead, attendees doubled their praise and enthusiasm for Gates. While admitting to being a trickster, for Gates, the gesture came from a genuine place. He admitted that becoming Shoji Yamaguchi freed him to make better pots. He internalized his own mythology to the point where he “began to believe that the institute was real.” But more to Gates’ main conceptual point: claiming a Japanese alias allowed the audience to experience his work through a different perspective. He added, “Yamaguchi allowed people to read the Japanese part of myself.” I think it’s important to note that while Gates is not Japanese, he feels a deep connection to Japan and its culture. His experience studying under teacher and collaborator Koichi Ohara during an artist residency in Tokoname, Japan remains a very influential part of his practice. This closeness also clues him into a Western art world bias towards Japanese artists as the exemplar wielders of clay and the epitome of tradition.

Gates used culture in an intentionally provocative way to call out the inequities within the art world for artists of color, and specifically Black artists in the ceramic field. His alter ego Shoji Yamaguchi is a mirror to a biased, hypocritical art world that values certain kinds of artists and art over others. By then shattering the mirror, he also smashed expectations and made people reflect on the pieces of their assumptions.

Once we see past the story of Shoji Yamaguchi as a cheeky trick, we can appreciate it as an imaginative projection of what Gates wants to build in the world of art and art education—a community of artists, rich in different cultures, in which he can root himself. Shoji Yamaguchi also gave him agency to connect his own mix of ideas, traditions, and narratives, which expanded possibilities within his own practice. As a mixed Japanese American artist who also has trouble finding representation in the traditional white dude canon of art history, I feel inspired by this mythology-turned-manifestation of belonging. I wish this artist community in Mississippi existed too. I know I’m not alone here.

Plates Convergence sparked a larger, conceptual project for him. Gates wanted to find more figures in ceramic art history that he could feel connected to and inspired by. In a 2014 performance talk entitled, Yamaguchi Soul Manufacturing Corporation and a Potter Named Dave: The Need for Blackness in Contemporary Ceramics, he asked this question: “How do we expand the field not only in terms of the ideologies that govern how we make and the things that we make, but how do we make the field more inclusive?” He then showed photos of an archival project of 60,000 glass slide images gathered from the University of Chicago and the Museum of the Art Institute, explaining:

“We’ve been combing them looking for images of ‘the other’—any other, anybody other than a Western canon of anything. This collection of glass lantern slides has become a kind of refuge, a kind of interesting repository of anomalies. If you comb long enough through culture, you find these anomalies pop up. I feel like I’m always trying to figure out what to do with these anomalies and how to link them to the world that I live in, to the things that I believe in. So I decided that I would look at the glass lantern slides, comb through, and find my history of ceramics as I was thinking about one dude. A dude named Dave.”

Dave the Potter

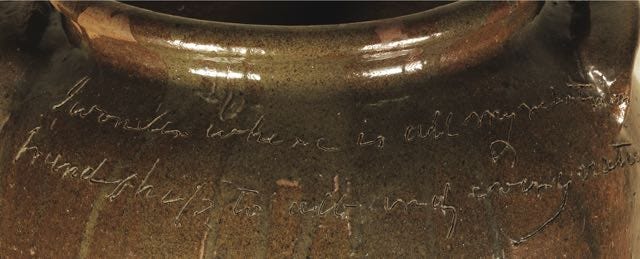

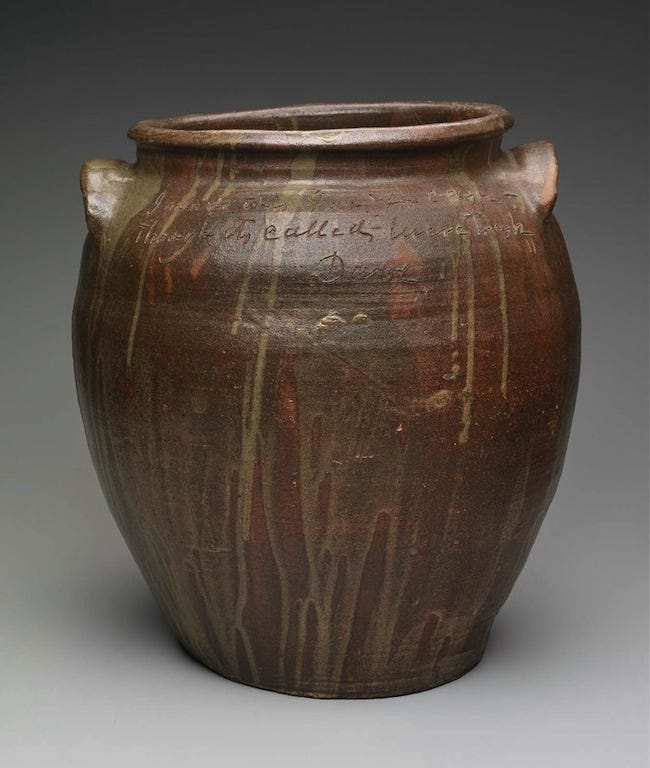

This “dude named Dave” is Dave Drake (~1800-1870s), also known as Dave the Potter, who created stoneware pottery and more notably, inscribed his own poetry onto his work. He was from South Carolina, and enslaved first by Harvey Drake, the owner of a large pottery business. He was one of 76 known enslaved people forced to work in Harvey Drake’s twelve pottery factories. It was illegal to teach enslaved people how to read and write, and it’s unclear as to how Dave Drake learned. Poetry certainly enhanced his craft and set his work apart, but at considerable risk. There was a 17-year period where he didn’t inscribe his pots with couplets, as to not draw attention to himself during higher times of tension. He lost his leg at an unknown point in his life—some speculate as severe punishment for writing on his pots. In addition to his writing abilities, throwing 45-gallon pots with one leg was an incredible feat, even with assistance from another potter. After the Civil War, he chose Drake for his surname as a free person.

The inscription reads:

Lm Aug 16 1857 Dave

I wonder where is all my relation

Friendship to all and every nation

Scholars and museums (even Antique Roadshow) celebrate Dave the Potter’s work and legacy, especially in the last 20 years. His work is part of the collections of the Smithsonian Museum of Art in D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, as well as other museums in South Carolina. Today his pots are worth around $40,000-50,000 and in 2020, he set a record $369,000 auction price for one of his inscription jars.

Theaster Gates also strives to keep Dave Drake’s legacy alive. In 2010, Gates reinterpreted his work through an exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum entitled, To Speculate Darkly, Theaster Gates and Dave the Potter. This exhibit emphasized performance and community building alongside the actual objects. As tribute to Dave the Potter, he featured a gospel choir and created a soundscape with musicians from Chicago. He collaborated with local crafts and tradespeople to create original pieces. He further developed historical connections to culture, craft, and labor through the Arts/Industry residency at Kohler Arts Center in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. From his own words:

“I wanted to embody Dave the Potter. To sing his name as if it were mine, to build a noble jar, and to celebrate deeply with the American craft tradition that was my first training. I was familiar with the lore of Dave, but decided to use his invitation to more deeply investigate the complexities of history-making in the absence of narrative, the speculative nature of history, and the ability to conceive of an exhibition based on a singular historical artifact: a pot.”

What does it mean for Theaster Gates to embody an imagined mentor, Shoji Yamaguchi, and a historical guide, Dave the Potter, and weave those narratives into his own? It’s a powerful way to recalibrate the artistic canon and shine light on forgotten stories—the “anomalies” buried by time and neglect. And what is the canon anyway, but subjective, western/white-centric values deemed sacred? Gates pays homage to the culture of Shoji Yamaguchi and to the life of Dave the Potter, but ultimately he moves to evolve ceramic art practice through collaboration. Both figures are creative partners and extensions of himself. In his work, he links these ‘anomalies’ in art history to strengthen the chain to the present. He creates opportunities for other underrepresented artists, in the hopes that future generations will have to comb less through their past to find themselves—to widen the canonical margins into the main lanes, where the anomalies become the main characters.

Gates as a Bridge

I don’t know if you can tell, but Theaster Gates means a lot to me. I studied art history at the University of Chicago, around the same time he started collaborating with the school to create stronger relationships and public programs with its surrounding South Side neighborhoods, such as the Arts Incubator in Washington Park. He continues to create many educational and artist residency programs within abandoned buildings he renovates in this area. This month, he just announced the inaugural cohort of the Dorchester Industries Experimental Design Lab, a three-year incubator project for creators in fashion, design, furniture, architecture, and industrial arts. While it’s been a long time since I’ve called Chicago home, I still think of him as a hometown hero. When I taught art last year, my classes discussed his piece, Minority Majority in our unit about protest art. And now writing this, I realize I keep returning to his work to remind myself of the potential and power of art born from bridging communities past, imagined, present, and future.

Enough of what I have to say! If you want to learn more about Theaster Gates in his own words, check out his 2015 TED Talk.

At the start of all this, I thought having an alter ego would be nice to hide behind if and when things heat up on the internet. But in the process of researching and writing, I discovered that the alter ego isn’t actually about separating yourself or shielding who you are from the rest of the world. In terms of the artists we’ve discussed, the alter ego is a way to multiply your creative possibilities. It’s a source for worldbuilding and mythology to build community. It’s a bridge that connects different parts of your experiences together to reveal deeper truths. It’s a trusted friend.

Thanks for reading. May brings us into a new theme and intersection to dive into. I’m pumped!

My first reading of this week's submission left me with the impression of, "Oh, No! A person must never misrepresent himself or make up a story about his past." We might notice that misrepresentation happens in the realm of politics. However, rereading opened my eyes and mind. "The gesture came from a genuine place...[he] allowed his audience to experience his work through a different perspective." Yes, it's Art! Through his narrative, Gates paid homage and called attention to another artist whose actual story, as much as can be known about it, will not be forgotten. May we all remember those like Dave the Potter. And may we all remember the lesson taught by Theaster Gates.