The Inimitable Eminem and Emin

The B-side to Track 02 // Vol. 01: The Case for Alter Egos

Recap:

Woof, it’s been quite a week writing back to back tracks! I wanted to keep this idea going, so here is the follow-up to yesterday’s post: Will the Real MF DOOM Please Stand Up? In this Part II, the B-side, I’m throwing Eminem and Tracey Emin into the intersection along with MF DOOM. We’re still thinking about the artist’s connection to the audience and the alter ego’s relationship to vulnerability. Hit Play.

Extended Play: MF DOOM x Slim Shady x Tracey Emin (Continued)

Slim Shady, the Gateway Drug

My entry point to hip hop was through mainstream radio, MTV, and BET later on after our cable switched. I didn’t know about MF DOOM when he was releasing pivotal albums in 1999 through the aughts. I wish I had! At that time, I was watching TRL religiously after school, right when Eminem started blowing up.

The first time I remember encountering an alter ego, outside of Superman and Clark Kent, was in Eminem’s 1999 music video for “My Name Is.” In the video, Eminem, as his alter ego Slim Shady, writhes in a straitjacket on his psychiatrist’s couch, played by a bespectacled and judgemental Dr. Dre. A TV flips through different channels and shows Slim Shady as absurdist caricatures of Bill Clinton and Marilyn Manson, a ventriloquist's dummy, a mad scientist, and all 9 floating heads in “the Shady Bunch.” The video swerves back and forth to scenes of Slim Shady, unleashed onto the world, wreaking havoc on anyone who crosses his path.

At the time, I didn’t quite understand the relationship between Marshall Mathers, his real name, Eminem, his rap name, and Slim Shady, his alter ego. To me, they were all equally angry and intense. However, Slim Shady appeared as the agent of chaos just goofy enough to get away with doing some pretty alarming things. He incited anarchy and controversy, provoking the worst in people in songs like “Guilty Conscience” (1999). For the next decade, Eminem stuck to an album release formula where the lead single would feature Slim Shady in another farcical music video—an unforgiving, grotesque funhouse mirror to the absurdity of the pop culture zeitgeist.

In addition to “My Name Is,” the videos for “The Real Slim Shady” (2000), “Without Me” (2002), “Just Lose It” (2004), and “We Made You” (2009) all incorporate the same irreverent elements of chaotic pop culture characterizations, Dr. Dre cameos, and the kind of “it’s just a joke bro”-flavored, MTV-endorsed misogyny and homophobia, all tied up with a slapstick bow. Ironically, Slim Shady, in his denouncement of pop stars, is a pop star himself. Eminem’s alter ego is the marketable version of the rapper, the cheat code to commercial success. The silly Slim Shady lures you in to find Eminem at the end of the album, the serious lyricist with the most laurels and yet nothing to lose.

While Slim Shady eviscerates celebrity culture by parodying its most overexposed stars, Eminem always sets himself at the first target. Never giving an opportunity for anyone else to weaponize his own shame, Eminem’s discography reveals his darkest details to discomfiting extremes. In his song “Cleaning out My Closet” (2002), he chronicles the cycles of abuse in his life. He raps:

I got skeletons in my closet

And I don’t know if no one knows it

So before they throw me in my coffin and close it

I’ma expose it

The video switches between painful childhood flashbacks, scenes of repentance, and a grown-up Eminem burying his coffin-shaped past in the rain. In “The Warning” (2009), a real-life diss track to Mariah Carey after she denied their romantic involvement with a savage video for “Obsessed,” he describes his own–ahem–humiliating moment in the boudoir to graphic detail. He addresses her directly, “if you’re embarrassing me, I’m embarrassing you, don’t you dare say it wasn’t true.” Eminem protects himself by controlling his narrative—taking it to the point where no one dares to follow or question its validity. It must be true, why else tell a lie about yourself that cringe?

The Beef and Mom’s Spaghetti

That said, it’s hard to embrace that kind of vulnerability when it’s delivered as a warning shot. Eminem still maintains his hard exterior even when revealing embarrassing, “emasculating” experiences. While this feels in some ways inaccessible, he still lets us into his life. We may not understand exactly who he is, but we get where he’s coming from. Eminem’s mythology is a classic underdog story, from the trailer park to the Grammys. He relates to his audience in how he eschews fame. In interviews, he still conveys that scrappy sensibility–nothing to hide, nothing to lose. This is also exactly what makes him the most intimidating rapper to face up against.

Eminem’s history of conflicts and celebrity beefs is extensive, but few would actually dare challenge him to a rap battle. Some chalk his unassailability up to his mind-bending lyricism. I argue that Eminem’s strategy to “overshare” makes him unbeatable. A great example of this happens in the final rap battle in his semi-autobiopic 8 Mile. As the underdog B. Rabbit battling the champion Papa Doc, he spends two-thirds of his allotted one and a half minutes dissing himself, his crew, his girlfriend, and his lifestyle before completely exposing his opponent’s hard persona as phony. “What’s a-matter dog, you embarrassed? This guy’s a gangster? His real name's Clarence.” His opponent chokes. There is nothing Papa Doc can say that hasn’t already been said and his credibility is destroyed beyond hope of redemption.

When you’re that powerful, no alter ego needs to protect you. I feel the same way about artist Tracey Emin.

The Exquisite Shame of Tracey Emin

Shame is a delicacy. While you might not have a taste for it, you know it comes at a cost, so it must be savored. We find our own shame repulsive, but we find it exquisite in others. When thinking about Eminem’s winning strategy to own and share his shame, I thought of another master confessor, Tracey Emin.

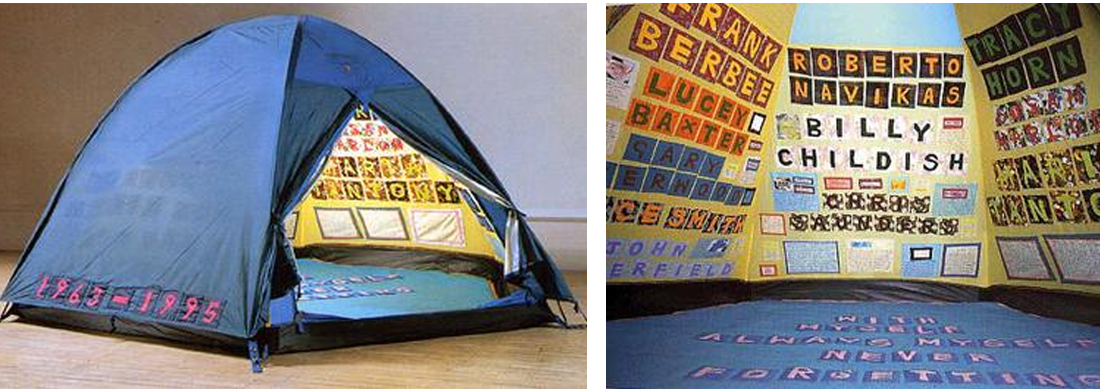

Tracey Emin is a celebrated and controversial British artist known for her visceral, autobiographical representations of sex. Emin exposes her every pain, shame, and trauma—memorializing them through personal artifacts and abstracting her memories onto paper and canvas. I learned of her work, “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With” (1995) in college, and it has lived rent free in my mind ever since. Oddly enough, it’s a tent!

For this piece, Emin appliquéd all the names of her 102 bedfellows from 1963 to 1995 inside of a nondescript camping tent. (It’s not all sexual though, some of the names were people she just slept with, like her grandma.) The lettering of the names inside look crafty and childish, a discordant sweetness in what is otherwise a spicy subject.

Another famous work of hers, “My Bed” (1999) is an installation of the bed she spent four days lying in after a bad breakup-turned bender. The bed is full of experience— disheveled and unmade, surrounded by empty liquor bottles, littered tissues, an ashtray full of cigarettes, condoms, period-stained clothing, a pregnancy test, and slippers. (To quote Megan Thee Stallion, “Real hot girl shit.”) She emerged from this bed and acknowledged it as her lived art. She was nominated for the prestigious Turner Prize for this installation in 1999. While she didn’t win, the art world attention and media frenzy that followed launched her career to new heights.

Is it safe to say that in 2022, we’re post-shock art? Haven’t we seen it all? And yet, I still feel such a visceral reaction when I engage with her art. In 2019, her exhibit entitled, A Fortnight of Tears debuted in London’s White Cube. The pieces in the show addressed her own life traumas with rape, a botched abortion, the death of her mother, and struggles with insomnia through paintings, sculptures, photographs, and film. Her canvases feature her bared body, legs spread, masturbating and bleeding—a drippy, jarring kind of reclining nude stylized in hasty, gestural lines. Through this exhibition, she reflects, “What this whole show is about is releasing myself from shame. I’ve killed my shame, I’ve hung it on the walls.” I read this, and I think of shame like a fungus, growing in dark private places, decomposing rot. Bringing it into the light kills it.

The Black Cat Woman

I read one article by The Guardian that described Tracey Emin’s alter ego as The Black Cat Woman, referring to her 2008 painting and tapestry, Black Cat. Both works depict a semi-nude woman, with a black square obscuring her face. She stands, hands between her legs. Her opened dress unravels into drips; her feet wade in a pool of bright red, which usually reads as blood. It feels disturbing and sexy, but somehow impersonal without the context of Emin’s own life experiences. There is little written about the series featuring this alter ego from my internet research—apparently it’s “brilliantly dark,” but I’m less curious about The Black Cat Woman, and more drawn to the unbound intimacy of Tracey Emin.

At the start of writing this week’s posts, I assumed that the alter ego was the ultimate liberator for the artist. MF DOOM built his own worlds according to his values, free from the music industry that betrayed Daniel Dumile. Slim Shady provides comedic relief from Eminem's painful past. But as witnessed through Tracey Emin’s art, killing your shame is the truest freedom, isn’t it? To destroy shame requires a private confrontation and a public act of vulnerability. In the aftermath of this kind of death, I’m left wondering—what else can grow in the space of letting shame go?

Thanks for reading this week’s double dose of The Drip.

You made it to the end, so your reward is a Venn! (A product of re-watching a lot of Eminem videos and listening to Jameela Jamil’s podcast I Weigh in the same week.) Also, a plug to follow me on Instagram @elspethmichaels! Have a great weekend.

TIL Mariah Carey made a diss track against Eminem, video parody and all. Incredible