“If it hadn’t been for art, the Civil Rights Movement would have been like a bird without wings. The people made it real through action.”

—Rep. John Lewis

In honor of Martin Luther King Day, I wanted to share a story about the late Rep. John Lewis and his connection to art, his mentor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and his lifelong fight for civil rights. It all started with a comic book.

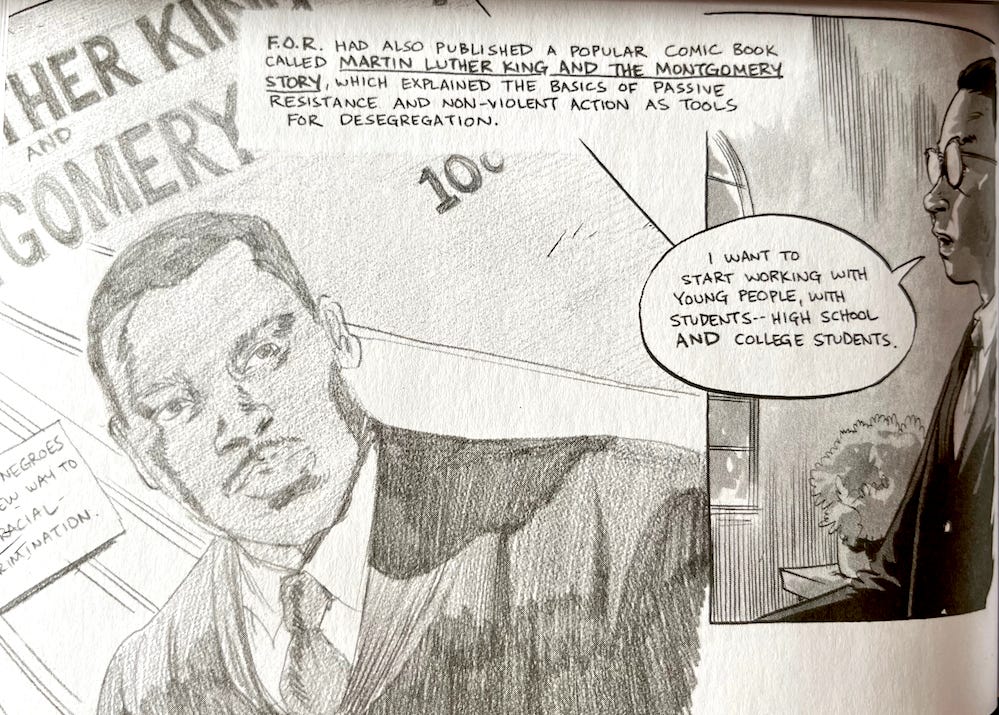

In 1957, Alfred Hessler and Benton Resnik collaborated with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. alongside illustrator Sy Barry to create a comic book called Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story. Hessler, the publications director of the social justice organization Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), proposed the idea after the Montgomery Bus Boycott to educate young people in the South about Martin Luther King’s origin story, how community leaders organized the 13-month bus boycott in Montgomery, and the tenets of nonviolent resistance. Using the examples of Mahatma Gandhi and Christian values, Dr. King explains “The Montgomery Method” and outlines steps for others to implement in their fight for freedom.

The comic book focuses on Dr. King’s message of nonviolence, especially in its intent to connect and influence a younger audience, but it’s important to remember that his radicalism was layered, multi-faceted, and transcended pacifism. Dr. King penned his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” in 1963, in which he calls for urgent, direct action against injustice, confronting segregation, racism, and prejudice with sit-ins and marches to force the issues to a point where they could not be ignored. He writes, “I am not afraid of the word ‘tension,’” after stating,

“We had no alternative except to prepare for direct action, whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and the national community.”

If you’re interested in reading Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story, here’s the 16-page pdf.

The Fellowship of Reconciliation printed 250,000 copies of the 10-cent comic book and distributed them to churches, schools, and civil rights groups. In the years that followed, the comic book guided many young activists in staging their own nonviolent protests, like Hollis Watkins and Curtis Elmer Hayes who sat at Woolworth’s segregated lunch counter in McComb, Mississippi, and Ezell Blair and Joseph McNeill who staged boycotts in Greensboro, North Carolina. The ideas they read in this comic book helped launch the sit-in movement across the segregated South in the 1960s.

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story also inspired a young John Lewis, who read it with his friends. In 1957, he wrote to Dr. King and met him before he went to college, the beginning of an inspiring mentorship. In Lewis’ words via The Atlantic:

“I saw King so many times afterward—-during the end of the Freedom Rides and during our efforts to desegregate places all across the South. He inspired me. He lifted me. He was a brave and courageous person, and when you would listen to him speak or talk to you, you were ready to go out there and put your life on the line, because he made it so plain and so clear that it was the right thing to do. He taught me to be hopeful, to be optimistic, to never get lost in despair, to never become bitter, and to never hate.”

In this video, John Lewis describes how this comic book moved him in his youth:

“I was greatly moved by—what we called then, a comic book, called Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story. It was all about the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Dr. King helped edit the story. It inspired so many of us. It’s a way of reaching everybody, in seeing a painting, a picture, a copy—it helped to make people real.”

Not only did this comic book spread ideas of nonviolent resistance within the Civil Rights Movement, its message spread globally. A few years after it was published, Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story made its way to South Africa, where activists shared the comic book with those resisting Apartheid. Soon after, the Fellowship of Reconciliation translated it into Spanish for distribution in Latin America. In line with their work opposing the Vietnam War in the 1960s and 70s, FOR also translated it into Vietnamese as an organizing tool for protests in Vietnam.

In 2008, fifty years after it was initially published, a human rights activist in Egypt, Dalia Ziada, spearheaded its translation into Arabic and Farsi as she believed it would help educate people throughout the Arab Spring protests. Using the framework she learned in the book, she managed to get it through censors in Egypt and circulated the Arabic edition into the crowds. (To hear more about her and her connection to this comic book, check out this WBUR article.) Zainab Al-Suwajj, the Executive Director of the American Islamic Congress, confirmed the comic book’s success in 2011 stating, “It has a huge influence…I’ve seen it many times with our young activists — holding it in Tahrir Square during the demonstrations to get rid of Mubarak and during the revolution.” (Via American University Radio wamu.org)

In 2013, Rep. John Lewis, took a page from his hero’s comic book and created his own autobiographical graphic novel series called March. Since Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story inspired him as a kid, he also adapted his life in illustration as a way to reach young people.

In this Wired article he states:

"It tells the story in such a dramatic way—it's not just the words. It's the dramatic images…It’s another way of reaching people who might not ordinarily pick up a regular book to read the story and be inspired by the story."

Committed to the accessibility of this project, Lewis made these books digitally available and DRM-free (media without digital rights management), and participated in Humble Bundle sales where purchasers could determine the price they pay.

The first volume of the March series references John Lewis’ first encounter with Martin Luther King and The Montgomery Story:

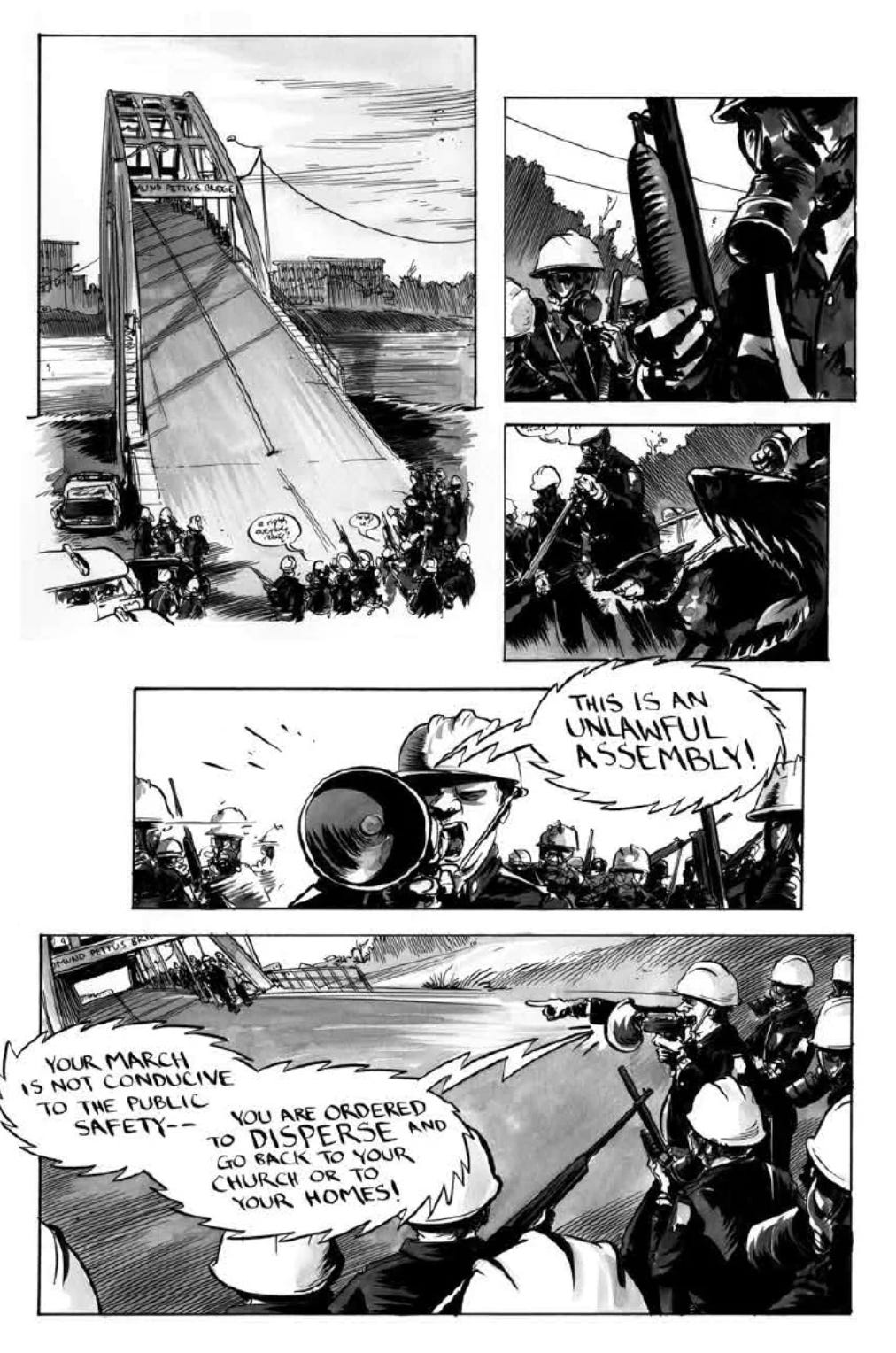

It also chronicles him in 1965, leading the first of three marches from Selma to Montgomery on the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

In 2015, as part of the release of the March Book Two, Lewis promoted it at Comic Con and led children in a reenactment of the marches from Selma to Montgomery, “cosplaying” as his younger self.

Lewis’ graphic novels are now used in classrooms, (including mine when I was teaching!) as educational tools to teach about the Civil Rights Movement, contributing to the legacy of the comic book that influenced him as a young person.

Let’s return to the context when Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story was originally published. A comic book was an unorthodox way of disseminating radical information and tools to organize, especially during a time when this kind of knowledge wasn’t readily accessible. Its message also spread hope. As this comic book has been adapted for modern use digitally and cross-culturally alongside many of Dr. King’s principles, I wanted to include this Vox article that was shared with me as I was editing this essay. In Don’t ask what Martin Luther King Jr. would do today and then ignore his real message, author Fabiola Cineas addresses the practices of misappropriating and whitewashing Dr. King’s messages especially through social media. She argues that Dr. King “can’t solely be defined by pacifism or confrontational action” and quotes Janai Nelson, associate director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, driving this message home:

“What we should be remembering about King is that he was in no way, shape, or form a pacifist. He believed in nonviolence. He believed in a tradition of sustained protests. And he also believed in full truth and transparency about the evils of white supremacy.”

Lastly, I adapted this post from the MLK Day lesson I taught in 2021 to my drawing and graphic design classes. I wanted my students to consider the possibilities in their art and youth—and the stories we experience through them—as tools to inspire others to enact change and as sparks to start movements. Illustrations bridge information and emotions where words lack. Picture and comic books are often the first kinds of exposure children have to art, and in many cases, how they first fall in love with drawing and find value in creative expression.

I created this lesson as part of a unit on art and activism inspired by this quotation by Toni Cade Bambara, which I’ll end on here:

“The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible.”

- Toni Cade Bambara

Thanks for reading.

Where can we find your 2021 MLK Day lesson?

Absolutely *loved* hearing about this comic. Thank you so much for sharing!