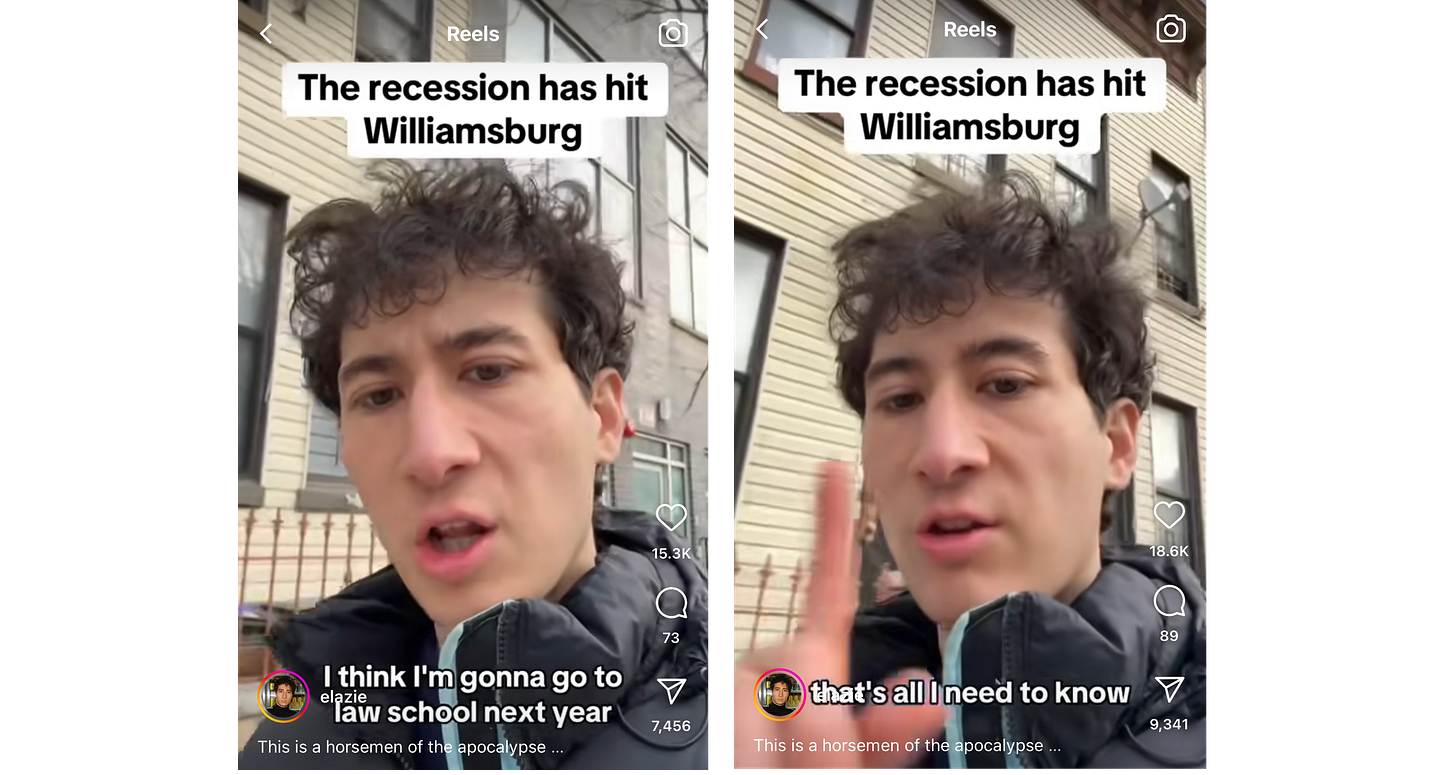

When I see content about “recession indicators,” I’m consuming it with horror and gusto. Not the actual economics of it all—I’m talking about office-siren, trad wife hemlines, upcycling, and underconsumption as fashion trends. Tinned-fish over raw bars at bougie restaurants. Lady Gaga ‘reheating her nachos’ for her latest album, Mayhem earlier this year. And now, Ke$ha is back. Klarna as a paying option on DoorDash, where yes, you can officially put that guac on layaway. And this stunning observation:

If you, like me, entered the job market during or in the aftermath of the 2008 recession, perhaps you share a similar spine-tingling reaction to the word. It’s a whisper on the wind uttered by a haunted 21-year old in a statement necklace and peplumed going-out top: R~E~C~E~S~S~I~O~N. I want to run away and scream, but I also need to know where the sound is coming from?!

It’s hard to distinguish if these pop culture recession indicators actually reflect an economic outlook, or if they’re just trends circling back on their natural orbits. Planet Fashion returns after 20 years, snatched in a fierce but familiar asteroid belt. Pop stars after a lengthy discography get sucked into black holes of nostalgia. We’re almost at the 20-year anniversary of the last recession—some trends from the late-aughts are due to resurface regardless. But again, I’m not an economist! As a human whose formative years happened to be during the aughts, I see what I see, and that explains all my blindspots, biases, and the half-life of my references.

But maybe the symptom also points to the cure. My own analysis of late-aught music trends brought me back to the club, apartment parties, and sticky frat floor basements. The pop soundscape was littered with the party animal-likes of LMFAO, Ke$ha, 3OH!3, and Cobra Starship. It was neon nonsensical, music made for the dance floor, the present moment, and a good time only. No jobs and crippling student debt? “Gonna be ok,” Lady Gaga told us, “da-da-doo-doo JUST DANCE.” It’s 2025 and Gaga returns with less reassurance, instead offering an ultimatum in “Abracadabra.” “The category is—dance or die.” We didn’t call it “recession pop” then, but Spotify lists it as a genre now. Apparently when things get bad, we return to the dance floor. Spotify daylist, a mirror to the soul, read me to filth! This is a common algo-rhythm for me:

When I dive deeper into more aughty trends from the dance floor, I think of my college roommate chanting the lyrics to “Independent” by Webbie feat. Boosie BBadazz and Lil Phat: “I-N-D-E-P-E-N-D-E-N-T DO YOU KNOW WHAT THAT MEANS?” In this memory, she’s singing with a hair straightener in hand, bobbing her head pigeon-like to each letter. (The true party always happened getting ready for the actual party.)

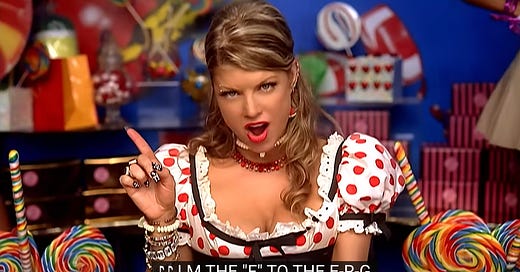

While spelling in song lyrics has a long tradition in popular music, in the aughts, it felt like an invasive flower blooming all over charts. Let’s start with Jay-Z’s “Izzo (H.O.V.A.)” in 2001. In 2003, 50 Cent only spelled the word ‘pimp’ in “P.I.M.P.” That same year, Gwen Stefani declared “The shit is bananas, B-A-N-A-N-A-S” in “Hollaback Girl.” Three years later in “Fergalicious,” Fergie and Will.I.am boldly rewrote ‘tasty’ as T-A-S-T-E-Y, but managed to uphold the traditional spelling of ‘delicious.’ (The same cannot be said of her 2006 album, The Dutchess, which seriously had me thinking for years that was how you spelled ‘duchess.’ A quick Google search confirms Fergie is in fact, not Dutch, but probably needed a way to distinguish herself from Sarah “Fergie” Ferguson, Duchess of York.) How could I also not mention “Glamorous,” where she spells out the title at the start of the song, and at the end of Ludacris’ verse.

In Fergie’s case, spelling is perhaps less of a trend as it is a trademark. (Or a compulsion?!) I’ll get to more examples, but these aforementioned songs were fun, catchy-as-hell ear worms. In most of these pop hits, spelling served as an onomatopoeic and inane filler device. You may not have known all the lyrics, but you knew how to spell bananas, and that was enough to be part of the zeitgeist. However, I’d argue that there’s more depth and purpose to explore in the lyrical spelling canon. I hear recent hits like Chappell Roan’s “HOT TO GO!” and “APT.” by Rosé and Bruno Mars and wonder, will we get more artists spelling in their songs? Please?

If we’re going into a recession, let me state for the record, that the only indicator I am requesting is the return of spelling in songs. DJ bring that back! Hear me out—lyrical spelling is not another harbinger of darker times returning, but rather, is a way we’re going to get through them. Now more than ever, we need spelling back in songs, where it belongs.

Spell for revolution. Say it with your chest.

Spelling words in song lyrics has a long history in popular music, but 1965 in particular, was a hallmark year for the micro-genre. Nat King Cole sang “L-O-V-E” as an acrostic poem, an enduring tune that finds its way into many a movie montage, wedding setlist, and cruise ship band repertoire. It was also in that year when Aretha Franklin belted R-E-S-P-E-C-T, laying out her demands and creating an anthem for the Civil Rights Movement. Originally written by Otis Redding two years prior, Aretha’s female perspective, passion, and pipes transformed it into one of the greatest songs of all time, or theeee number one if you ask Rolling Stone. (Otis’ version was great, obviously, but nothing touches Aretha’s version, especially with her adding the “sock it to me.”)

She writes in her 1999 autobiography, Aretha: From These Roots:

“It was the need of a nation, the need of the average man and woman in the street, the business man, the mother, the fireman, the teacher—everyone wanted respect. It was also one of the battle cries of the civil rights movement. The song took on monumental significance. It became the “Respect” women expected from men and men expected from women, the inherent right of all human beings.”

Aretha only spells ‘respect’ twice in the song, in succession towards the end. The instrumentation halts dramatically, punctuating Aretha’s vocals between R-E-S-P-E-C-T’s and their subsequent lines. The climax is in the vocal isolation, where Aretha strips the word to its parts, leaving no space for misunderstanding or ambiguity. It’s a sensual demand. It’s an invitation as a line drawn in the sand.

Spell for community. Participation is effervescent.

In 2024, the organizers at Lollapalooza moved Chappell Roan to a larger stage to accommodate the influx of fans planning to attend. She made history for garnering the largest audience ever for a daytime set. When I watched her performance clips, I wanted to be in that crowd, especially during her hit, “HOT TO GO!” She and her dancers spelled each letter with their arms, teaching the dance to the crowd before beginning in earnest. The camera drones flew over a massive crowd singing, dancing, and jumping, all in the name of spelling with their entire bodies. To truly spell-dance, you can’t hold your phone at the same time, and as much as I’m often the person recording my favorite songs at concerts, I loved to see their hands free, fully present in embodying the shapes of the words.

The most enduring example of spell-dancing originated with the Village People and their 1978 hit, “Y.M.C.A.” Growing up, this song was a multi-generational banger at most celebrations. We did it in gym class, school dances, weddings, and sports events. It was impossible to be too cool while doing the Y.M.C.A. It was an obligatory part of the party when our disparate groups came together to finally gel in a sequence of four letters. We marched during the verses, we lifted our arms up in exaltation at the chorus. But alas, legacies and associations change over time, leaving room for new classics. (For a deep dive on the song’s history and where it stands now, check out this Washington Post article.)

I think “HOT TO GO!” emerged at the perfect time as Gen Z’s contribution to the spell-dance. We need songs like this—ones that demand our whole bodies to participate, where we come together in community and collective effervescence. One dance to unite us all. Take off your cool.

Spell for subterfuge. The girls who get it, get it. (And get away with it.)

Spelling is a common way for parents of young children to communicate sensitive information to each other without the kids understanding. It communicates the concept but doesn’t implicate you in it. Before we cussed in earnest, we probably spelled the words we weren’t allowed to say. Spelling is a cheeky loophole.

In 2009, Britney Spears released “If You Seek Amy,” off of her album, Circus. Leading up to the chorus, she declares some variation of “…all of the boys and all of the girls are begging to if you seek Amy.” It doesn’t make grammatical sense, only to further emphasize that it sounds like “F-U-C-K, me.” While it was novel for me at the time, punny variations of spelling “F-U-C-K” in songs did not originate with Britney.

According to this 2009 Slate article, “If You Seek Amy’s Ancestors,” there have been several songs titled “If You See Kay.” The first example recorded was in 1963 by blues pianist Memphis Slim. (You can find a longer list here.) But if we’re crediting the true originator for “If You See Kay” look no further than James Joyce’s poem in Chapter 15 of Ulysses (1922).

If you see Kay

Tell him he may

See you in tea

Tell him from me

Read the poem out loud and see if you can find the other naughty word spelled out. Shakespeare himself also spelled that same word in Twelfth Night, and also added…potty humor?

By my life, this is my lady’s hand. These be her very c’s, her u’s, and her t’s, and thus makes she her great p’s. It is in contempt of question her hand.

From Shakespeare to Britney, sneaking in vulgarity like this stretches language in playful ways. In Gabe Henry’s book Enough is Enuf: Our Failed Attempts to make English Easier to Spell, he explains how the quirks of the English language create absurd spelling and also pun-tastic opportunities.

“Interestingly, this is what makes our language good for punning. The heart of our problem, linguists tell us, is this: English has 44 sounds but only 26 letters. To make up for those missing 18 phonemes, some letters are forced to work multiple jobs.”

This playfulness also inspires other ideas for the potential of language and the rules that bind it—grammatical and otherwise. Can we push the pun past play? Maybe we can’t always say things explicitly. Maybe we need to turn to more subversive strategies when the very idea of freedom of speech is warped, when the message must transcend censorship. Can we adapt our use of language in ways that comply on the surface but contradict at the heart? Can we spell what we mean and still communicate what we stand for? If you see Kay, tell her we’re trying.

Spell for intimacy. There’s a lot riding on it.

Earlier this spring, as I was stringing a lot of these ideas together, I attended my nephew’s first spelling bee. It struck me how emotional and high stakes a bee can be. And also, how odd English is. In Enough is Enuf: Our Failed Attempts to Make English Easier to Spell, Henry recounts the 500-year history of the Simplified Spelling Movement, championed by the likes of Ben Franklin and Mark Twain. Henry writes, “There’s a reason why spelling bees are common in English-speaking countries: English spelling is absurd.”

I asked one of my dearest friends Jackie about her experience competing at the National Spelling Bee (not once, but twice!) when she was in middle school. (She has since completed a PhD in English Literature and is the most eloquent speaker I know.) She wrote a beautiful email back to me about it:

“I think for a lot of spelling bee kids (myself included) a part of the appeal of the bee—the endless practice, the etymological deep dives, the highly educated, high-stakes guesswork—is the way that it fosters a profound intimacy with language.”

“The way that spelling fosters such an intimacy with language is by zooming in and embracing a perspective that is closer than our usual vantage point, thereby defamiliarizing words as structures.”

This idea of spelling fostering this intimacy with language makes so much sense when put like this, and yet, we rarely return to this foundation. As we advance in our education, connection to language grows into the sum of its parts. We learn how to read and spell to build a vocabulary through which we eventually craft poems, stories, and essays. We’re further pulled from this close vantage point with technology created to offload the ‘burdens’ of language. I think about how ChatGPT saves us time processing information, but also distances us from our own gritty attempts at the written word. I see the predicative text that appears in my email drafts, and yes, it’s usually spot-on, but it also suggests a kind of doubt to my original choices. And don’t get me wrong, I’m so grateful for auto-correct, which saves me every time I have to spell ‘separate’ (don’t ask!!!) but lessons strengthen from mistakes. Auto-correct did not save me from writing “for all intensive purposes” in a college paper and I will forever remember the correct phrase because of the mortification and laughter that resulted from my professor’s corrective comments.

This intimate connection to language feels important to encourage and protect, especially when post-pandemic reading levels are down and screen time is up. We’re seeing examples of AI in schools as a double-edged sword, granting faster access to more information, while also stunting the critical thinking skills to interpret it. Book bans and budget cuts to education and public programs round out this bleak outlook.

In all my recession indicator content engagement, I’ve come to appreciate that they aren’t just signs pointing to an economic downturn. They can also be a societal movement towards the way we soothe ourselves in anxious times, escape the dread, and/or find solutions. We always turn to art for this, as a mirror to the current sentiment. Is it a stretch to argue that spelling in pop songs is a balm to our collective, broken soul? YES AND YET I will take anything that positions language as a tool for revolution, critical thinking, community, and play. Bonus points when music is incorporated as a mnemonic device to bake it all in. And this brings me to present a childhood favorite, Arthur, and my favorite episode, “Arthur’s Spelling Trouble,” where he learns how to spell ‘aardvark’ by rhyming over a slick 90s beat. (A formative TV moment for me.)

My nephew’s spelling bee had me at the edge of my seat, clutching my sister’s hand each time he got up to the microphone. Like many of his classmates, he practiced so hard for the bee in the weeks leading up to it. Seeing their efforts made my heart burst. We rooted for everyone on stage and cheered every time a kid expressed the rush of surprise and pride at spelling the word right. There’s also an intimacy in the shared experience of it all—the swell of support, the nerves of competition, sportsmanship in defeat, and the glow of accomplishment.

I left the bee feeling that it’s easy to take for granted on all that rides on our words. We always have the option to look up meanings, request more context, and ask to hear it one more time. There is so much at stake when we risk ambiguity and reject the opportunities to clarify communication.

If one student hadn’t asked for the definition, she would have been slayed by a night instead of finishing as runner-up.

Thank you to my dear friend, Dr. Jacqueline Kellish for sharing your spellsperiences. And thank you always, dear reader, for reading.