Lady Pink's Sublime Subways

Track 08 // Vol. 02: PINK

Radio Edit:

If you’ll indulge me, I’d like to wrap up May’s theme, Volume 02: PINK, a few days into June. Welcome to the intersection of art and vandalism. We’re kicking it back to the origins of hip hop and celebrating the trailblazing graffiti writer, Lady Pink.

Extended Play:

Historically, the origins of hip hop break down into 4 elements: DJing, MCing, break dancing, and graffiti writing.

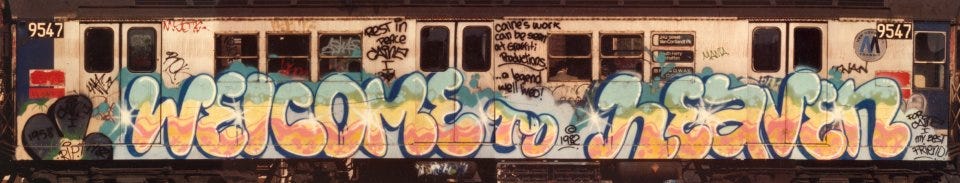

All four expressed different facets of the youth culture that overflowed from the Bronx during the late 70s, evolving further into the 80s. In the beginning, the founders of hip hop, DJ Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa (and a little later Grandmaster Flash), hosted neighborhood dance parties for MCs and b-boys/girls to flex their skills and develop their styles, creating events that built community through loud celebrations. At the same time, graffiti writers moved secretly in the shadows, risking their lives to tag, or ‘bomb’ subway trains—the city’s snaking canvas—forcing millions of people across boroughs to witness their audacity. Their messages, for as long as they lasted within the competition of space, created shifting power dynamics within crews, and a pseudonymous fame in the public realm. Graffiti’s polarizing debate—is it art or a crime?—agitated New York in new ways, a city that never slept to begin with, now fortified with the new high of aerosol.

Hip hop as a language began with DJs splicing music to create song breaks—the percussive sweet spots that lured people to the dance floor. Think of this as the syntax. MCs strung words to the beat that break dancers punctuated through popping and locking. Graffiti writers transcribed these messages into loud, colorful letters that further abstracted with the speed of moving trains. They risked it all for the speed—the faster tempos, the blur of spinning limbs, the eager, pressurized release of paint. The graffiti sub-culture emerged as the visual pillar of hip hop with the help of several key figures, one of whom being Sandra Fabara, aka Lady Pink.

Track 08 is about Lady Pink. Risk it all to represent something greater than yourself. Spray it to say it.

I first encountered Lady Pink’s work last spring, when I broke my COVID museum fast at Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip Hop Generation at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. I went for Basquiat, but stayed for the work of his pioneering contemporaries, graffiti artists like Fab 5 Freddy, Futura, Lee Quiñones, Zephyr, and Lady Pink. While Jean-Michel Basquiat became the breakout wunderkind of the early 1980s street art scene in the Lower East Side, the strength of this exhibit showcased the power of the crews and collaborations that ignited the art form from all over New York City. I especially gravitated to the surreal style of Lady Pink. Drawing inspiration from nature and her childhood growing up in the Amazon, her warm, rosy color palette and organic shapes set herself apart from the darker, more angular lines of her peers. Her work drew me in also because of her name and how clearly it defined her place as a woman among a very male-dominated space.

In Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation, author Jeff Chang chronicles Lady Pink’s origin story. Born in Ecuador and brought up in Queens, Lady Pink started painting subway trains in 1979, tagging her boyfriend’s name ‘KOKE’ after his parents sent him back to Puerto Rico, as she describes, “for being naughty.” To enter the dangerous world of the train yards, she had to fight through the social barriers before getting through the physical ones.

“I was getting sexism from ten, twelve-year-olds saying that you can’t do that, you’re a girl. It took me months to convince my old homeboys from high school to take me to a train yard. They were not having it. They were not taking some silly little girl into danger like that. So I had to harp on them and convince them and finally they said, ‘Fine. Okay. Meet us inside the Ghost Yard.’ They left it to me to find my way in there and meet them inside.”

The Ghost Yard was a huge train depot built on top of an old graveyard, located at 207th Street along the Harlem River. She adds:

“I had to prove that I painted my own pieces. Because whenever a female enters the boy’s club, the world of graffiti, immediately it’s thought that she’s just somebody’s girlfriend and the guy is putting it up. But they’re not gonna believe that some girl is strong enough and brave enough to stand there for that period of time and do something big and massive and colorful. They just think that she’s on her knees and bending over for the guys. And that’s the kind of word that went out about me and goes out about every single girl that starts to write. So you have to stand strong against that kind of adversity and that kind of prejudice…”

The misogyny alone took a lot of tenacity to overcome. Once she proved that she was ‘down with the boys,’ she then faced the threat of police, competition from rival crews, and the perils of painting in precarious places like elevated tracks and tunnels. Every night, as a self-described “uncontrollable teenager,” she would jump 10 feet out of her window with spray cans, meet her friends in subway tunnels or train yards, paint in darkness until morning, and sneak back into her house before her mother left for work. She did this from 1979 to 1985. In many interviews, including this feature in Fast Company, she talks about how she took risks not only to express her own art, but also to show young women that they could take their space in this world too.

“The feminist movement was catching up with me. Us girls were busy proving we could do anything the guys could do and there was no stopping us.”

The Namesake

How did Lady Pink get her name? In an interview with artnet, she explains the collaborative story behind it. ‘Pink’ was bestowed onto her by legendary graffiti artist and friend Richard “Richie” Mirando, aka Seen.

“My boy Seen—I came to school one day, and he was like, ‘this is your name now.’ Guys wouldn’t write it, because hip hop and graffiti were always very homophobic. It was well-known that Pink would be a girl, and they wanted to be known around the city as the only group with a girl.

I titled myself, that I chose. I used to read a lot of historical romances about European nobility, duke and duchess this, and marquis that. So I titled myself Lady Pink, because we were royalty. We had the most popular table. They treated me like a queen. I’d snap my fingers, some kid would go fetch me food. That was high school…”

To see Lady Pink in action in her early days, check out Wild Style and Style Wars, two of most iconic and foundational films about graffiti. Wild Style (1983) is a fictionalized story of young graffiti writers from the Bronx, played by the main artists of the time, Lee Quiñones, Fab 5 Freddy, Zephyr, Lady Pink, and founding father DJ, Grandmaster Flash. Style Wars (1983), is a PBS documentary about hip hop that captured key cultural moments in the world of graffiti as they unfolded. This clip below shows a conversation between Lady Pink and fellow graffiti artist, Cap, as they discuss the conflicts between him and other artists. (He would tag other artists’ burners—larger, elaborate pieces that require more time than a quick throw up, almost immediately after they finished them.)

Lady Pink x Jenny Holzer

Lady Pink entered the fine art world at a young age, exhibiting in galleries at 16, partying with the likes of Andy Warhol at 17, and presenting her first solo show at 21. The appetite for street art demanded more consumable forms, by the way of accessible, transportable canvas. One of my favorite parts of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation, featured her collaborations with Jenny Holzer, a conceptual artist who also works predominantly in language, but in a very different way. From text-based projections of pithy advice, to socially-conscious headlines, Holzer started her career in public art by wheatpasting posters in the city at the same time Lady Pink was bombing train cars.

In 1983, Holzer invited Lady Pink to collaborate on a series of paintings that combined her murals with text from Holzer’s Survival series. Here are two of my favorites from the exhibition.

“TEAR DUCTS SEEM TO BE A GRIEF PROVISION”

“When you expect fair play you create an infectious bubble of madness around you”

Holzer’s detached words interlace with Lady’s Pink’s emotional subject matter. The contrast conveys an inviting, irresistible chaos. For a deeper dive into this series, check out MoMA’s mini-analysis of their painting, Trust visions that don’t feature buckets of blood, as relevant now as it was in 1983.

Personally, I don’t think enough people talk about how metal this collaboration is. How impactful it would have been to learn about this in any of the many art classes I took! (You’ll come to find that I feel this way a lot.) I have loved Jenny Holzer’s work ever since encountering her Truisms in college, but I never knew about her early collaborations with street artists. (Frank Ocean is also a fan.) Discovering Lady Pink and Jenny Holzer’s mutual admiration and shared values in this exhibit inspired me to learn more about their history and process. (If you’re interested too, check out their interview with the curators of Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation.)

What makes Lady Pink so important to me is her ability to bridge worlds, to exist in many intersections at once. She has created her own space within ‘high brow’ fine arts establishments and ‘low brow’ street vandalism, never severing the connection to her roots in public art. While her paintings hang in the collections of the MET, the Whitney, the Brooklyn Museum, and the MFA Boston, she continues to mentor and work with local schools to create public murals with kids. I admire the community and collaborations she continues to forge, while always maintaining her own voice and style. She expresses her heritage, cultures, and imagination in all of her pieces and asserts herself as a woman and feminist, while transcending identity labels. She is first and foremost an artist, a person who finds the most meaning in creating.

Pink Matter

Pink, in its most exact nature, is a dance between soft and hard. Lady Pink describes herself as a ‘big softy,’ even after a decades of fighting and putting her life on the line for her art. Underestimated for her petite stature and feminine looks, she pushed harder than her male peers to establish herself; her legacy endures because of it.

I think about two specific shades of pink that also illustrate this dance. First, Baker-Miller Pink (also known as Drunk Tank Pink), a bright Pepto Bismol shade believed to create a calming, weakening effect on people. In 1979, two naval officers, Gene Baker and Ron Miller, painted this color inside the cells of the U.S. Naval Correctional Center in Seattle to make their inmates less aggressive. For 156 days post-paint job, the facility was violent incident free. (It also found its way into the decor of opposing teams’ locker rooms for similar reasons.) Mountbatten Pink, is a pucey mauve that Lord Mountbatten painted on British battleships in the early 1940s to camouflage them during dawn and dusk, the most vulnerable times for naval attacks. (Shout-out again to The Secret Lives of Color by Kassia St. Clair.)

Pink is both a balm for calm and an agent of violence. A conflux of milk and blood. The edges of dawn, the gradients of gloaming. Pierce the eye, assuage the heart.

Thanks for thinking pink with me. Happy June, Happy Pride! Next week, we’ll kick off a whole new theme for the month.

Such a trailblazer! Lady P had to struggle for acceptance and inclusion on the streets and subways. She finds not only acceptance but acclaim as she collaborates with J. Holzer. Thus her art is elevated to world reknown galleries and museums.