In case you forgot, Michael Jordan finally retired from the NBA in 2003 wearing a Washington Wizards jersey. After two previous attempts at saying goodbye to the game, he returned for two more seasons with the Wizards after becoming a part-owner and their President of Operations in 2000. For all intents and purposes, his comeback was a business decision.

Of course we remember when Jordan first retired in 1993 after clinching the Chicago Bulls’ first three-peat. A short stint with minor league baseball and boom—in 1995, he announced his return with a two-word fax that read, “I’m back.” After adding three more championship rings to his hand, he retired again in 1999, having reached a global fame so omnipresent, he was revered as the greatest player of all time. But his final return in 2001 seemed less about the “love of the game” and more about filling seats. People paid attention, but it was a quieter, less triumphant comeback. He still wore the number 23, but his time in a Wizards jersey was largely unmemorable and unceremonious. Fake-out to fade-away. Did it hurt his legacy? No, but it definitely didn’t add to it. Michael Jordan’s 1998 championship win and second three-peat was too perfect and poetic of an end to then add an epilogue, a trilogy we didn’t want. Chicago Bulls or Tune Squad, no exceptions.

2003 was a hot year for retirement. After 9 multi-platinum albums, JAY-Z announced his hyped hiatus from rapping with his Game 6 jump shot-meets-magnum opus, The Black Album. Like MJ’s first two retirements, JAY-Z left while at the top of his game but didn't stay out of it for too long.

This month, we explored themes in ritualized endings: first with graduation, then intentional unraveling in romantic partnerships, and now in this final week, retirement. What are the potential rituals in ending a career? How do you control the narrative in process, but also, keep it intact after the work is complete? Is legacy about longevity or immortality?

Track 12 is about encores and their effects on legacies.

A couple of years ago, I read JAY-Z’s autobiography, Decoded, co-authored by dream hampton and published in 2010. As a nod to the nuances of interpretation, its cover cleverly features a golden Rorschach painting by Andy Warhol. When I finished it, I wondered what from his last untold decade he would add to this story. Maybe not much—I’d argue his best and most impactful work is stacked in the first half of his career, with the exception of Watch the Throne. This book has an interesting format: he breaks down his life thematically through song lyrics released from different albums, non-chronologically. As expected, it’s a controlled narrative that doesn’t necessarily demystify the human Shawn Carter, but like many self-produced artist memoirs and documentaries, we get a sense of how he wants to be seen and remembered. Decoded is a window into how he understands his own public perception and reveals what kinds of criticism he deems important enough to address. I’m curious to know if and how this has changed since its publishing.

We learn through reading Decoded that JAY-Z’s first album, Reasonable Doubt, was supposed to be his last in order for him to focus on building the business of Rock-A-Fella Records. As we know, the release of Reasonable Doubt was just the beginning:

“When I made my first album, it was my intention to make it my last. I threw everything I had into Reasonable Doubt, but then the plan was to move into the corner office and run our label. I didn’t do that. So instead of being a definitive statement that would end with the sound of me dropping the mic forever, it was just the beginning of something. That something was the creation of the character JAY-Z.”

By 2003, JAY-Z grew uninspired by hip hop. In a 2003 New York Times interview, he gave his reasons:

“Hip hop is corny now…The game ain’t hot. I love when someone makes a hot album and then you’ve got to make a hot album. I love that. But it ain’t hot.”

JAY-Z needed competition in order to fuel that creative engine, and admitted that his beef with Nas grew out of boredom. It was lonely at the top, hip hop hadn’t recovered in the absence of Biggie and Tupac. In JAY-Z’s own words about his retirement, he writes:

“When I announced plans to begin recording The Black Album, I said it would be my last for at least two years, and that story grew into rumors about retirement. I considered an all-out retirement out loud to the media, and that was a mistake even though I definitely gave the idea a lot of space in my head…When I first started planning The Black Album, it was a concept album. I wanted to do what Prince had done, release an album of my most personal autobiographical tracks with absolutely no promotion. No cover art, no magazine ads, no commercials, nothing: one day the album would just appear on the shelves and the buzz would build organically.”

If we take JAY-Z at his earnest word, this idea is kind of charming, right? To think that The Black Album would quietly emerge onto the charts instead of as the marketing behemoth it became is hard to imagine. JAY-Z’s “final concert” for example, was an unprecedented event in hip hop. He packed Madison Square Garden with fans and featured a roster of hip hop royalty. His ending ritual here is a mix of sports analogies. To begin with, Michael Buffer, the announcer for all boxing matches at MSG, introduced him to the crowd. He assumed the role of the MVP in his all-star team of collaborators/performers. He ended the concert by “retiring” himself, à la legendary basketball players, by sending his jersey up to hang from the rafters. He starred in the documentary, Fade to Black, memorializing the epic evening by splicing behind-the-scenes footage with this final concert performance.

No one truly believed JAY-Z would actually retire then, but even if he had, the strength of this album holds enough charge to light his legacy for a long time. Nearly two decades after its release, it’s still among his best work. His song “December 4th” crystalizes family lore into artist mythology. “What More Can I Say” is a brazen response for those who dare question his place among the greats. “99 Problems” approaches perfection with its tight narrative flow and an undeniably infectious hook. “Encore” is a celebration—JAY-Z teases fans to beg for more while giving himself an out to come back. He also links his greatness to Michael Jordan, a recurring theme throughout his discography:

When I come back like Jordan wearing the 4-5

It ain’t to play games with you

It’s to aim at you

It’s one of my favorite songs of all time. “Encore” video below:

In 2006, JAY-Z presented his equivalent of the 45 jersey as the album Kingdom Come. Rather than giving the lackluster critical recap, let’s just say The Black Album was a tough act to follow. Kingdom Come does not make the cut for his top five albums, but I have a soft spot for it, mostly for the song “Beach Chair.” As far as retirement goes, this track gives the greatest sense of finality out of JAY-Z’s entire catalog. It’s a slow-building, measured retreat, a sonic sunset that shimmers until the very end.

When put in context within the soundscape of the early aughts, The Black Album was born in a genre-bending time. Mash-up music, inspired by DJ-sets and house music, became increasingly popular. This technique to seamlessly transition songs evolved into unifying different songs as one experience in cohesive or delightfully incongruent ways. Within the same month of The Black Album’s release, JAY-Z and Linkin Park launched their collaboration EP, Collision Course, which featured 3 songs from The Black Album along with Linkin Park’s most well-known hits. “Numb/Encore” was its most successful track, the sum being catchier than its parts.

I listened to Collision Course a lot during the pre-vaccine days of the pandemic, as it featured heavily in the playlists for my “rage runs.” A rage run is more primal scream than cardio: *I’ve become so nuuuuuuuumb*

In early 2004, music producer Danger Mouse remixed The Black Album with The White Album by the Beatles, calling it yes, The Grey Album. I discovered this a few years after it was released in college, and I grew to love it almost as much as the original. It brought a new experience to an album that I replayed over and over again, and introduced the possibilities of the Beatles in hip hop. (It’s purely subjective but “Allure” mashed up with “Dear Prudence” on The Grey Album >>> the original “Allure” on The Black Album. Sorry Pharrell! Full album here.)

I bring this up because I believe we have a deep desire to multiply the possibilities for more experiences when confronted by the idea of a final work. JAY-Z created his own rituals to “end” his career at the time—a personal album projecting his legacy to the heights of Biggie and Tupac, a farewell concert, a documentary, a retirement befitting of a legend as big as Michael Jordan, and the fandom to pull him out of it at any point. The Black Album gained new lives within different genres of emo and classic rock and elevated the mash-up to unprecedented heights. We couldn’t let go of JAY-Z’s final work as it was. We hungered for more of its potential.

I think of artists who have died young, before reaching the retrospective era in their careers. Often without their consent, they get forced into the now-established ritual of creating posthumous final works, like greatest hits albums with “new!” unreleased tracks. As fans we want more music to fill the void, but I always feel conflicted about these kinds of albums and how it strips the artists’ agency over their legacies. For example, XXXTENTACION and Mac Miller, both young rappers who passed away in 2018, released albums in 2022—adding to their already growing posthumous collections of songs. These albums are usually demos frankensteined into more polished songs through heavy production lifts and features with living artists—again, harkening back to the Freudian uncanny version of something once familiar.

We can view these albums in multiple ways: a blatant money-grab by the artists’ estate, an intentional farewell, an opportunity to grieve and make final memories with a beloved artist. In my experience, these albums lack the quality and discernment of ones created during the artist’s life, and they spark debate about what we can include within the true oeuvre of the artist. That said, I yearned for more Amy Winehouse music after she passed away in 2011, and I consumed her posthumous album Hidden Treasures: Lioness with the same enthusiasm as Frank and Back to Black.

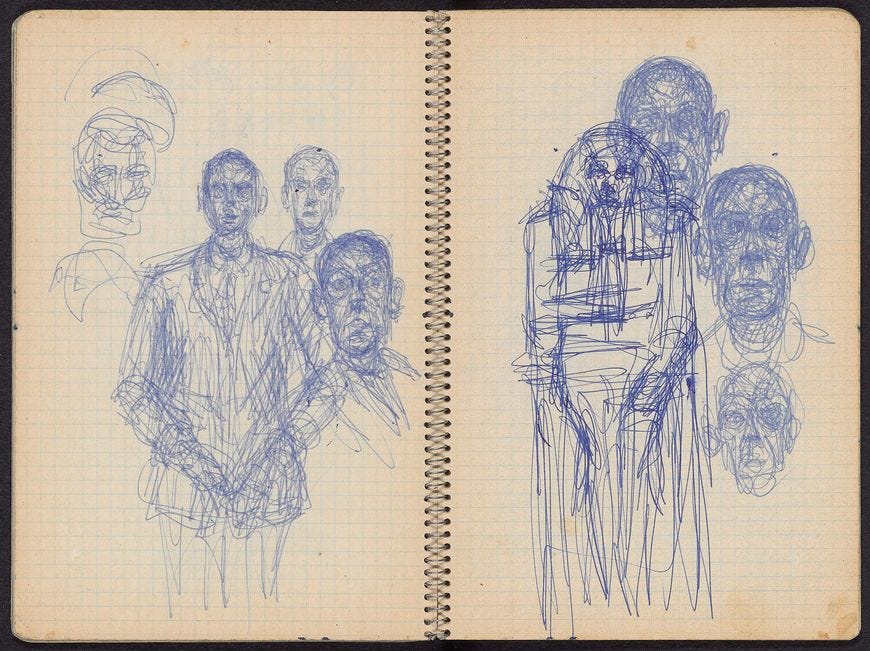

When I enter a museum exhibit and see old sketchbooks, letters outlining ideas, drafting plans, and underpaintings to a known masterpiece, it makes me appreciate the work more. To learn the process is to build a new intimacy and connection to the art. I wonder if we can understand the rough cuts and demos in a similar way to sketches—they still display mastery and perhaps, reveal more than the polished piece itself. We understand more of its truth and essence. Once an artist dies, the possibilities freeze in the finite unless we unearth hidden treasures, remixing them into new experiences. With all due respect to the deceased, we are in the age of the audio zombie: for some, the point of art is to transcend death.

I think back to the mastery of Michael Jordan, the same greatness, competitiveness, and ego that kept him at the top for so long lured him to come back for more. As part of the mandatory watchlist within our early pandemic zeitgeist, I watched The Last Dance completely immersed in the glory and nostalgia of the 90s Chicago Bulls dynasty. I loved reliving the same games I experienced live as a kid. Watching the practices, their process of achievement, the on-court dramas, and locker room manipulations was all very entertaining and fascinating. However, I couldn’t help but feel that the documentary ultimately detracted from Jordan’s image and legacy. Perhaps it’s a good thing to demystify the human behind the legend; no one really belongs on a pedestal. What is legacy if not an eventual form of mythology, of hero-worship?

It seems impossible for an artist’s intended legacy to remain intact after their death, even with a tattoo that spells it out like Anderson .Paak, or specific stipulations in a will, like in Lana Del Rey’s case.

Tampering with retirement, final works, and their ending rituals renders the intended legacy into fragments. Those fragments however, become fractals unpredictable in growth, shape, and possibility.

Thanks for reading. And now, we have just graduated from this theme. Next week I’ll introduce a brand new mixtape.

I really like your idea that posthumous albums are akin to artist sketches. I never thought of it like that before. Makes me appreciate them more.

As someone who passionately rooted agains the 90s Bulls, but later began to really appreciate how great Jordan was once he was retired ("they say they never miss you 'til you dead or you gone" as Jay says in December 4th), I sincerely and heartily rooted for him to have success with the Wizards. To see that play out, and then later on realize how much his Wizards teammates disliked him and how he destroyed Kwame Brown's psyche...I guess that serves me right