It’s been quite a summer so far, [cut to long montage of hellacious headlines set to the soundtrack from Requiem for a Dream], but thank goddess for the blessings bestowed by Lizzo and Beyoncé in July for making us feel less dead inside. Like you, like everyone, I’ve been playing Renaissance nonstop since it dropped. Last month, I wrote about JAY-Z’s creative connections to Jean-Michel Basquiat, which included the Tiffany campaign with Beyoncé and one of Basquiat’s paintings. So imagine my (our?!) delight when Beyoncé dropped another Basquiat reference in “I’M THAT GIRL,” the first track off the album:

Bring that beat in, now I can breathe again

I be beatin' down the block, knockin' Basquiats off the wall-all

That's how I ball

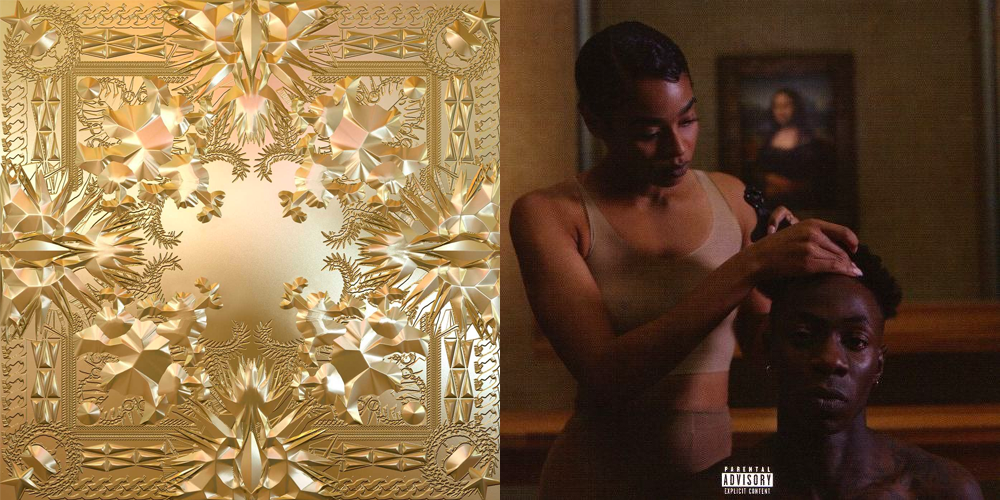

Listening to Renaissance and reading *the discourse* about the project’s featured collaborators, song authorship, and crediting samples sent me down the rabbit hole of tracing themes and sources of inspiration in her discography. In her album notes for Renaissance, she thanks “her beautiful husband and muse” JAY-Z, who isn’t featured on the album, but feels present in more romantic, lusty tracks like “PLASTIC OFF THE SOFA” and “VIRGO’S GROOVE.” (FYI the transition between both songs is one of the best things that has happened in 2022.) As collaborators, The Carters, and as each other’s muses in their solo projects, the intertwined themes in Beyoncé and JAY-Z’s work span across albums like back-and-forth conversations. One conversation like this starts with the song “That’s My Bitch” from Watch the Throne, and develops further in the video for “APESHIT” from EVERYTHING IS LOVE, JAY-Z and Beyoncé’s first full-length album as The Carters.

I will not be writing further about Renaissance the album here, but more about what it means for Beyoncé to stand next to Renaissance paintings.

In the last decade, JAY-Z and Beyoncé have referenced art history in their work as a measure of wealth and status and as a means to call out disparities in representation.

Track 15 explores the art and techniques that reframe Western art history. Have you ever seen a crowd going APESHIT…in the Louvre?

In the song “That’s My Bitch,” JAY-Z dedicates his verse to comparing his wife, Beyoncé, to a masterpiece. He directly calls out institutions like the Museum of Modern Art to stop reinforcing white beauty standards in favor of exhibiting more BIPOC women subjects and artists. He also brings the biggest art dealer in the world, Larry Gagosian, into this campaign, a man who wields enough power and influence in the art world to make (and break) careers.

Uh, Picasso was alive, he would've made her

That’s right [ ], Mona Lisa can’t fade her

I mean Marilyn Monroe, she's quite nice

But why all the pretty icons always all white?

Put some colored girls in the MoMA

Half these broads ain't got nothing on Willona

Don't make me bring Thelma in it

Bring Halle, bring Penélope and Salma in it, uh

Back to my Beyoncés

You deserve three stacks, word to André

Call Larry Gagosian, you belong in mo-seums

With Beyoncé as his muse, JAY-Z starts this conversation by asking, “...why all the pretty icons always all white?” As collaborators, they respond to this question together by literally taking over the Louvre in their video for “APESHIT.” Simply put, it is spectacular. Arguably one of their most epic videos out of both of their careers from a production standpoint, “APESHIT” is also one of their most impactful videos for its messaging. They package centuries worth of art criticism—not lyrically but visually— in a stunning 6 minutes.

I’m not begging you to watch it, but I’m also not not begging you to watch it. (…I’m definitely begging you to watch it.)

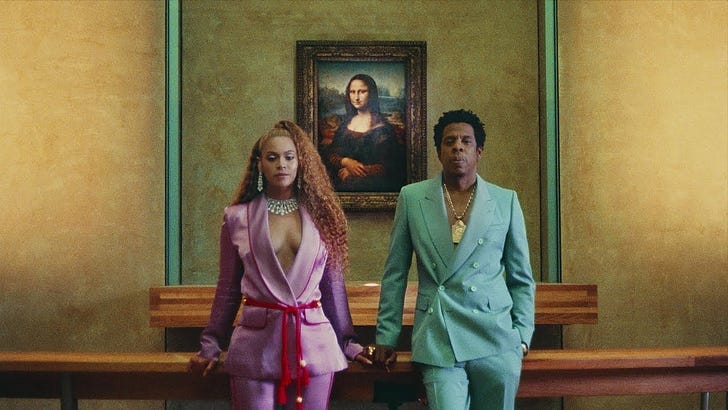

In the opening scene for “APESHIT,” JAY-Z and Beyoncé stand statuesque in front of the Mona Lisa, as enigmatic masterpieces themselves. Their presence alongside the most celebrated art in Western history—Winged Victory of Samothrace, Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, and Venus de Milo, to name a few—establishes them as peers to these iconic works and artists. Academic and cultural institutions like the Louvre historically have dictated canonical ideals of artistic value and beauty. As contemporary creators and as curators of culture, The Carters use this framework to assert that they are not beholden to it. They punctuate the video with scenes that spotlight Black figures in paintings, including Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s, Portrait of a Black Woman (Negress), making them the main characters in the Eurocentric and colonialist contexts that often neglected them.

Art historian Alexandra Thomas describes the video in this Time article, as “an embodied intervention of Western art.” She elaborates:

“Black women and Black women artists are excluded from the history of Western art, but their bodies, particularly sexualized or desexualized in domestic labor or sexual labor, are there. I think what really stuck with me was the juxtaposition of subject portraits of white womanhood…the Mona Lisa with the Negress painting and then we have Beyoncé intervening in this narrative and also being so unapologetically black about it too. Beyoncé and these other artists aren’t assimilating, but instead, staging this embodied intervention that disrupts more than it conforms to the logistics of Western art and Western museums.”

Thomas also makes an insightful point about how the Louvre, (and I’ll add, institutions like the Louvre) are spaces where “white people, Europeans, and Americans, go to really romanticize empire, to think about the genealogies of white male artists, and then we have Beyoncé, a Black woman, and her husband, dancing around…” Via Twitter, Thomas also directs us to Faith Ringgold’s quilt-painting, Dancing in the Louvre, which depicts young women dancing joyfully in front of the Mona Lisa, as a parallel to the scenes of Beyoncé with her dancers. Seeing these two images side by side makes my brain tingle. Both show a celebration, an uninhibitedness, a desire to express emotion through art and movement.

Faith Ringgold, a contemporary, multi-disciplinary artist famously known for her story quilts, creates work that rewrites historical narratives and centers Black women by combining personal memoir, African American culture, social commentary, and activism. Her aesthetic exudes a kind of modernism that breaks away from Western art traditions and techniques. In her autobiography, We Flew Over the Bridge, she writes about evolving her painting style:

“White Western art was focused around the color white and light/contrast/chiaroscuro, while African cultures, in general used darker colors and emphasized color rather than tonality to create contrast.”

As an activist, she has long fought for more women representation in art institutions. In the interview below she recounts:

“They would call the guys inside to sit around the table to talk to the curators and directors, you understand? But not me. ‘The museum will open up to African American artists, but you won’t be one of them ‘cause you’re a woman’…well I decided I need to get involved with women’s issues.”

To hear more about her art and activism, I’d highly recommend watching the video below. While Faith Ringgold’s work is not referenced explicitly in the video for “APESHIT,” her legacy and art continues to inspire the way for others to develop their own practices in reframing art history.

Back to the dancing! In the longest dance sequence of the “APESHIT” video, Beyoncé dances in a row of women, who are all dressed in nude bodysuits that match their skin tones, emphasizing the spectrum of shades between them. They hold hands in front of the enormous Jacques-Louis David painting, The Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon and the Coronation of Empress Joséphine on December 2, 1804, which depicts the ceremony where Napoleon crowns his wife after first crowning himself the ruler of France. At first glance, this scene establishes the Queen B to Queen Joséphine parallel, but with more consideration, it addresses a deeper critique on how women’s bodies are represented in museums. Let’s consider the female nude.

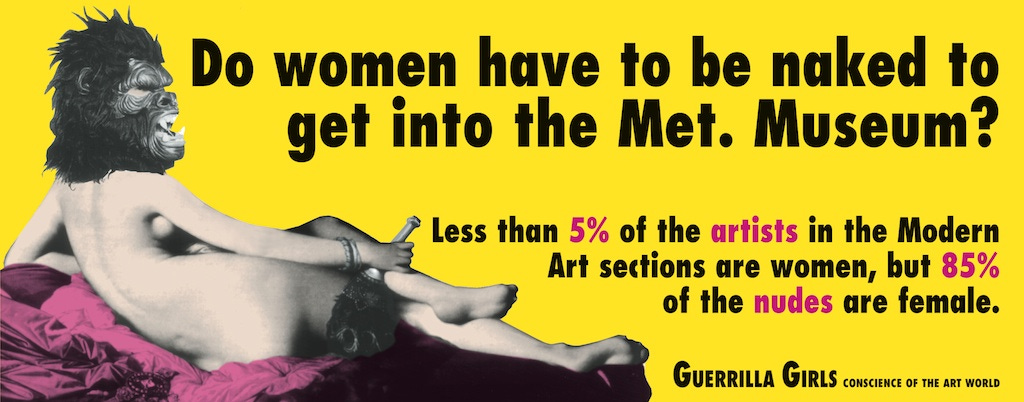

In the 1980s, the activist artist collective Guerrilla Girls, created a project called The Guerrilla Girls Talk Back. They surveyed the collections of museums like The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Whitney, analyzed their records on exhibiting women and BIPOC artists, and created posters criticizing the institutions’ failings. This poster was one of the most cited ones from the project:

To me, “APESHIT” confronts this canonical idea of the female nude. “Nude” as a word means naked, but its meaning as a color has a long history of being a kind of beige, communicating that the default color of skin is that of a white person. This idea gets reinforced from the color of band-aids to the names of crayons. I remember coloring with a Crayola crayon called “flesh” as a kid; the color was a light peach. Band-Aid and Crayola have since rectified this, but those implicit signals of white supremacy root deeply into a person’s psyche when exposed at a young age. In “APESHIT,” the dancers’ clothing creates a nude illusion that is not intended to satisfy the male gaze but rather, to communicate that ‘nude’ is a spectrum of colors.

In other scenes, the dancers lie on steps, pointing to another version of this trope—the reclining nude, where in paintings, a woman would lie or swoon seductively, usually set in a biblical or mythological context under the flimsy guise of allegory. (It’s not porn if Zeus shows up, right?) The choreography is sensual however, again, not configured to the male gaze. The dancing also becomes frenetic, like the crowds they describe seeing from the stage. Juxtaposed with the masterpieces in the Louvre, the dancers’ movements connect historical narratives to the present day—as if the statues come alive to tell us that we only know half the story. They activate the surrounding art by inhabiting this space, reframing them into a non-Western, contemporary context.

The video’s true power lies in how it uses juxtaposition as a technique to reframe visual narratives in art history, contributing to a greater conversation in calling out representation and visibility within art institutions. Beyoncé and JAY-Z point out the rich cultural histories of African and Indigenous civilizations simply by standing next to the Sphinx of Tanis. Why do we keep experiencing art through the warped lens of colonialism? The context here is crucial—The Carters are not re-contextualizing narratives—they’re spotlighting what’s always been there, in plain sight.

I’d like to wrap up by introducing one more artist who also creates work that critiques and reframes art history, Titus Kaphar. His 2017 TED Talk, “Can art amend history?” is my favorite of all time; I’ve assigned it as homework and built lessons around it. He tells a hilarious, personal, and poignant story about how he found himself in art history.

In his art, Kaphar uses cutouts and whitewash techniques to “amend not erase” history, to add focus on neglected Black and Indigenous figures in historical paintings. In his talk, he explains that visibility is not just what is seen—we perceive it also in the lack of scholarship and information accessible:

“Historically speaking, in research on these kinds of paintings, I can find out more about the lace that the woman is wearing in the painting—the manufacturer of the lace, than I can about this character here.”

He refers to the character in the painting below/left, Shifting the Gaze.

Faith Ringgold, Guerrilla Girls, Titus Kaphar, JAY-Z and Beyoncé create art that “shifts the gaze,” “intervenes and disrupts,” and opens worlds of untold stories within the institutions that historically confine them. It’s not just about the seeing and showing. It’s also about questioning curation in exhibits and curriculum, engaging critically, blazing new research trails, restructuring the methodologies and values long taught without amendments, and unlearning what we just accepted from “higher” authorities. (Woof, I’m trying!)

I love museums and what they do to support education, creativity, and communities. My experiences visiting and working in them have shaped so much of how and what I’ve learned about the world. A form of loving something is to hold it accountable.

Thanks for reading.

Love your perspective and your integration of concepts across genres and communities alike. 😎❤️

Good stuff in this one! Really enjoying these, even if I'm not always commenting!

Hope you're having a dope summer!